What Is the Additive Manufacturing Process?

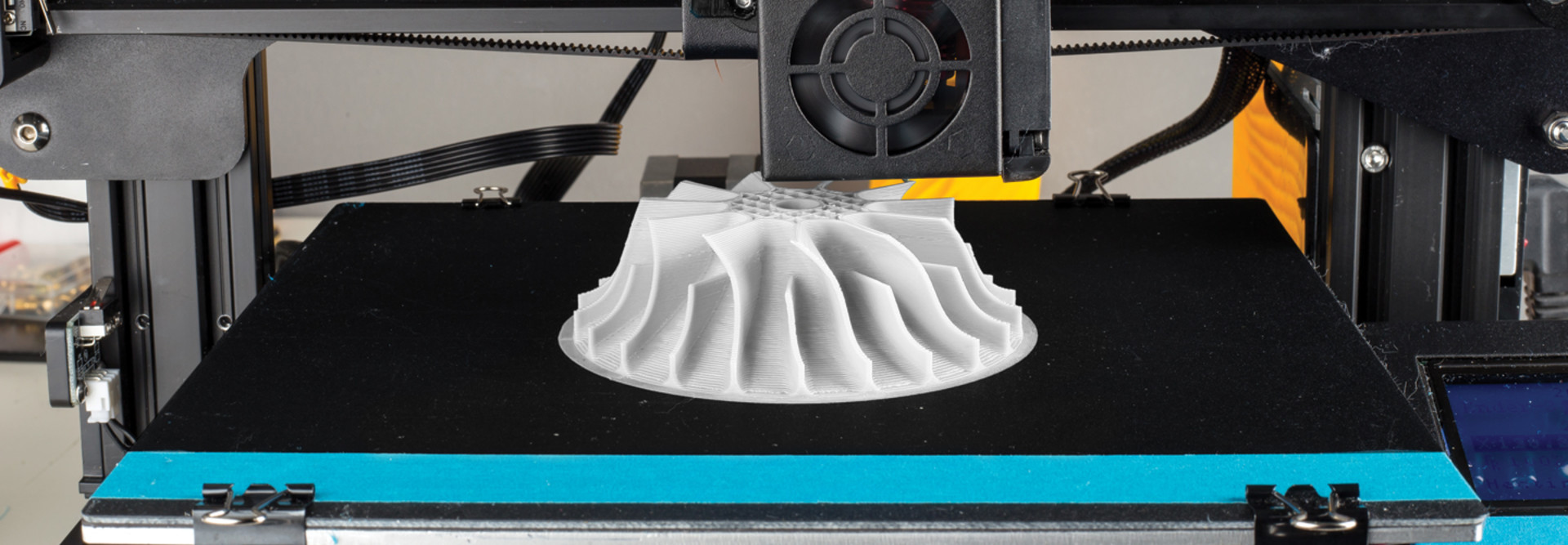

As 3D Hubs notes, “producing a digital model is the first step in the additive manufacturing process.” This is accomplished through CAD.

CAD, Autodesk notes, “is technology for design and technical documentation, which replaces manual drafting with an automated process.” CAD is an engineering technique, and not just a drawing tool or a suite of software, Jason Schuler, a robotics engineer in the exploration research and technology programs at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, tells FedTech.

Instead, CAD can be seen as a design philosophy or technique that lets users go from a whiteboard concept to a digital model, in which the fit and function of something can be manipulated, all the way to a final product.

The next critical phase is the conversion of a CAD model into a stereolithography (STL), which uses polygons to describe the surface of an object. 3D Hubs reports:

Once a STL file has been generated, the file is imported into a slicer program. This program takes the STL file and converts it into G-code. G-code is a numerical control (NC) programming language. It is used in computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) to control automated machine tools (including CNC machines and 3D printers). The slicer program also allows the designer to customize the build parameters including support, layer height, and part orientation.

From there, 3D Hubs notes, print materials are loaded into 3D printers and printing, often automated, can begin. Some additive manufacturing tools require the removal of prints and post-processing.

MORE FROM FEDTECH: What is a digital twin and how is it used in government?

Additive Manufacturing for the VA Builds Prototypes, Prosthetics

For Dr. Beth Ripley, director of the VHA 3D Printing Network at VA Health Care Systems, additive manufacturing is driving the development of five functional “buckets”:

- Assistive technology: From 3D printed solutions for brain injuries to fishing rod adapters, assistive technology is “custom designed for veterans to interact maximally with their environment.”

- Pre-surgical planning: Leveraging additive manufacturing makes it possible to “extract and create a near-perfect replica and then put it into the hands of the patient and the surgeon to plan the perfect course.”

- Orthotics and prosthetics: This specialized field focuses on the development and creation of custom-built lower limbs or upper extremities.

- Custom dental solutions: 3D-printed dental solutions improve patient outcomes and reduce the risk of complications.

- Bio-printing custom implants: As noted by Ripley, these custom implants are designed to help veterans achieve a sense of normalcy. Additive manufacturing paves the way for “next-gen solutions that add in things like electronics or sensors to provide additional information.”

There are many benefits to additive manufacturing for the VA. “Added complexity is free with 3D printing,” Ripley says. “While tooling in traditional manufacturing ramps up costs very quickly, this isn’t the case for 3D printing. Instead, you just need the design.” As a result, it’s possible to build complex, strong and lightweight structures without increasing costs.

The Veterans Health Administration uses 3D printing to solve a wide range of problems.

Ripley also points to the use of additive manufacturing to help doctors provide physical representations of more abstract medical concepts. “Doctors aren’t very creative in describing things,” she says, “so it’s often done in reference to a vegetable — pea-sized, walnut-sized, watermelon-sized. But what does that really mean? Physical representation gives autonomy back to the patient and lets them advocate for themselves.”

For Ripley, additive manufacturing isn’t simply a performance-improving process but a potential opportunity. “While 3D printing is a manufacturing technology that we’re bringing into the walls of the hospital,” she says, “what we’re really doing is creating a new profession.”

READ MORE: Find out how federal IT leaders can adapt to accelerating technological change.

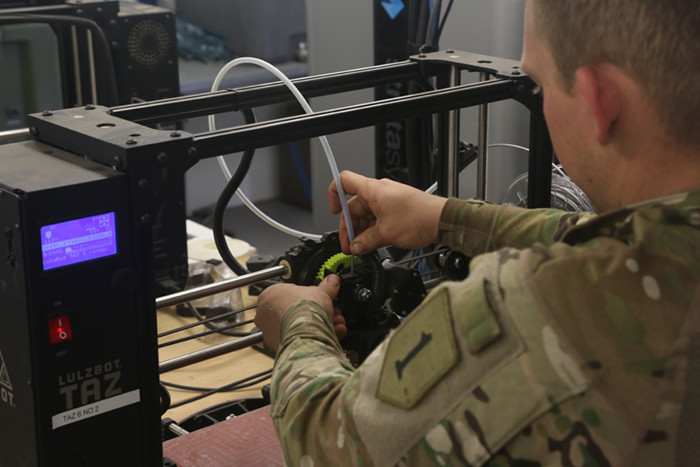

Parts Manufacturing Drives 3D Printing for the Army

In the Army, additive manufacturing is now being used by agencies including the Tank-automotive and Armaments Command (TACOM) and the Ground Vehicle Systems Center (GVSC) to improve operational readiness and increase supply chain effectiveness.

According to Phil Burton, program manager of advanced manufacturing at TACOM, the agency has two strategic goals.

“First, augment supply chain responsiveness in the strategic support area today leveraging the capability of the Rock Island Arsenal Center of Excellence, and second, empower forward advance manufacturing capability of the future Army at the tactical point of need in the operational and tactical support area as technology develops, reducing the sustainment tail while increasing readiness,” he says.

Additive manufacturing offers the opportunity to do both. In practice, this means that TACOM is “adopting advanced manufacturing incrementally with the vision to expand indefinitely.” To determine which parts take priority, TACOM uses a set of three groups or “echelons.”

- Component echelon: According to Burton, these parts are “select readiness drivers, are obsolete, have no technical data packages, have no source of supply and are of immediate need.”

- System echelon: System-echelon parts are those with historical demand but are not currently on backorder; their 3D data will be obtained and “vaulted” for future use.

- Program echelon: These parts are “being identified to support modernization and future Transition to Sustainment requirements by our Program Executive Offices (PEO) partners via contract language and new programs.”

On the GVSC side, meanwhile, teams are “focused on trying to use additive manufacturing to get after components that either have a very long lead time or are stuck without a source,” according to N. Joseph Kott III, GVSC branch chief of materials: additive manufacturing.